Learning Center » Knee

Patellofemoral Syndrome

This typically results from wear of the under-surface cartilage on the knee cap. Pain often becomes worse navigating stairs or jumping (which increases forces through the knee cap). Physical therapy can be helpful (especially with inner-thigh muscle strengthening) to help prevent the kneecap from sliding to the outside. If there is improper alignment of the leg, then the only effective treatment is surgical re-alignment. Sometimes steroid injection into the knee reduces inflammation, but is usually only a temporary relief. Surgical treatments are limited, and attempts to restore cartilage through procedures (microfracture or carticel transplant) meet with limited success.

Jumper’s Knee

This is an overuse injury to the patellar tendon (connection between the knee cap and shin bone). Stair climbing and jumping often worsen it due to increased forces through the patellar tendon. Physical therapy, activity-modification and bracing can be helpful.

Prepatellar Bursitis

This is inflammation of a fluid-filled sack in the front of the knee. These sacks (bursa) are normal throughout the body and serve as a lubricant between skin, bone and muscle. When the sacks become inflamed, the recommendation is to avoid mechanical irritation (such as hitting it on things) and take anti-inflammatory medications. If this approach is ineffective, steroid injection into the bursa can sometimes be helpful. If the sack becomes infected (septic bursitis), it may require intravenous antibiotics in the hospital or surgical debridement.

Osgood Schlotter

This is a self-limiting condition where there is pain below the knee cap of an active adolescent. It is thought to result from overuse of the knee with constant pulling on the growth plate where the knee cap tendon attaches to the tibia (shin bone). It usually goes away with decreased activity and use of anti- inflammatory medications. Sometimes it persists until maturity when the growth plates close.

Dislocated Knee Cap

When a patient describes a knee dislocation, it is often a patella (knee cap) dislocation. Typically the kneecap slides to the outside of the knee and usually goes back into place on its own. If it is the first time this has happened (and there are no loose fragments in the knee), then treatment is non-surgical. Gradual range of motion, bracing and physical therapy (emphasizing quadriceps strengthening) is the mainstay solution. For recurrent dislocations, surgery may be the best option. I typically perform a reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament which connects the femur (thigh bone) to the knee cap on the inner side of the knee. This structure helps tether the knee cap so it doesn’t slide to the outer side of the knee. If there is a major mal-alignment of the leg, then re-alignment procedures may need to be considered.

OCD

Osteochondral defect is when a piece of surface cartilage in the knee becomes loosely connected or breaks loose and floats around within the knee. This can cause pain and locking or catching of the knee, when performing certain range-of-motion movements.

MRI is typically the best way to diagnose the condition. In adolescents, OCD may heal on its own (if cartilage is still attached). If the fragments have broken loose, then arthroscopic repair can be attempted. If the piece cannot be repaired back into place, then a cartilage restoration procedure may be indicated. (microfracture or carticel).

Microfracture can be done in one procedure arthroscopically, and involves placing holes in the bone to encourage bleeding and healing at the site to fill in with a scar-cartilage.

ACL Tear

The ACL is a bone-to-bone connection between the femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone) that helps prevent sliding of the tibia when twisting or changing direction while running. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries typically occur with a “plant and twist” mechanism, so there does not have to be contact from another athlete. Sometimes this happens when a basketball player lands awkwardly after jumping. Typically there is immediate swelling of the knee due to an artery that feeds the ACL bleeding into the joint.

You can live without an ACL, as long as you do things in a straight line. When you change direction, you start to miss the ACL and there is subsequent instability of the knee. This is why athletes can’t play sports without an ACL.

Bracing is an option for non-operative treatment to try and mimic the ligament function. For active people, I typically recommend reconstruction of the ligament to facilitate returning to sports or other recreational activities. Another consideration for surgical intervention is determining if there’s a second injury in the knee (typically a meniscus tear) that can be repaired at the same time as the ligament reconstruction. Continuing to play sports without a functioning ACL increases risk of developing arthritis, due to abnormal forces the knee takes on. Even with reconstruction, there remains increased risk of arthritis, likely due to cartilage damage sustained in the original injury.

There are two options to choose from for ACL surgery (also called a graft). The first option involves using tissue from your own body (autograft). The other option is to use tissue from someone who has passed away (aka cadaveric or allograft). I offer both options to my patients. There are pros and cons to each, and I encourage patients to make their own decision.

Allograft has a risk of disease transmission from the donor. That risk is estimated to be one in 1.5 million. Allograft also requires more time to incorporate into the patient’s bone after surgery. The advantage with allograft is a shorter surgery and less pain immediately after surgery.

For autograft, I use hamstring tendons, which provide the strongest graft according to laboratory studies. Autograft has the obvious advantage of no disease transmission risk, but involves a longer surgery and risk of some knee-flexion weakness (though not noticeable by most people). Long-term studies show there is probably no difference in function between autograft and allograft. Rehab begins one week after surgery and I do not use a brace after surgery. Patients are usually on crutches for two weeks. Typically I don’t allow cutting or contact sports for six months after reconstruction.

MCL Tear

The medial collateral ligament connects the femur (thigh bone) to the tibia (shin bone) on the inner side of the knee. It’s typically torn when the knee is buckled toward the opposite knee. This is rarely treated with surgery since it heals well on its own. The most difficult thing in the first few weeks is stiffness of the knee. With a small tear, sometimes you can resume sports in one month (depending on symptoms and physical examination). Sometimes it is helpful to wear a hinged knee brace which helps facilitate range of motion while preventing unwanted buckling of the knee inward.

PCL Tear

The PCL is a bone-to-bone connection between the thigh bone and shin bone, which helps prevent backward sliding of the shin bone. Posterior cruciate injuries are typically sustained during a force on the front of the shin bone pushing backwards (such as a dashboard against the knee during a car accident). The CL can be treated without surgery most of the time (unlike the ACL). Rehabilitation focuses on quadriceps (thigh muscle) strengthening, to help stabilize the knee. I typically reconstruct the PCL only when there are multiple ligaments torn in the same injury.

Cartilage (Meniscus) Tears

There are two menisci in the knee, one on the inner side (medial) and one on the outer side (lateral). The medial meniscus is the one most commonly torn. There is typically inner knee pain, sometimes with catching, clicking or even locking of the knee in a given position. It is common to experience a gradual increase in pain over months or even years. If the meniscus is torn acutely, it usually doesn’t swell until the next morning.

Arthroscopic surgery to repair the cartilage is what we usually try for in most young patients. Partial removal of the torn fragment is the other main treatment option. In young patients with an irreparable tear and no arthritic changes in the knee, a meniscus transplant is an option. After partial removal of a torn meniscus fragment, patients are on crutches for up to one week, followed by therapy and return to work/sports in about four to six weeks.

Iliotibial Band Syndrome

The IT-band is a muscle that starts in the pelvis, crosses the hip and extends below the outer-side of the knee. This can become inflamed and painful either at the hip or the knee. It is often associated with a sudden change in training (such as a sudden increase in mileage for long distance runners). Therapy stretches and ultrasound treatment over six weeks may calm down inflammation. Otherwise, a steroid injection can be performed as a strong anti- inflammatory measure.

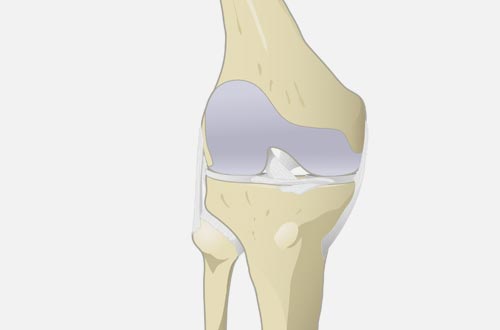

Osteoarthritis

This condition occurs when the surface-covering cartilage (that cushions the joint) erodes and exposes bone. There is inflammation combined with loose fragments and pain. For mild to moderate cartilage loss, therapy and anti-inflammatory medications can be helpful.

If pain continues, then we consider injections. Steroid gives the most immediate relief, as an anti-inflammatory, delivered directly into the joint. Newer injections (called visco-supplementation) attempt to relieve pain by replenishing lubricating and nourishing substances in the arthritic knee. These usually are given once a week for three to five weeks, and take a few weeks to see results. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections are also an option, though most insurance will not pay for this.

If none of these treatments are effective, surgery is the last resort. For younger, active patients with arthritis only on the inner side of the knee, I sometimes suggest a partial knee replacement. For more extensive arthritis, total knee replacement is typically the best option. I now offer uncemented total knee arthroplasty which avoids the use of bone cement which can potentially decrease the stress of surgery on the body and hopefully lead to better longevity of the implants.

Before surgery, a three-dimensional map of the thigh bone and shin bone is created with imaging that allows the surgeon to plan out the precise placement of the implants before the day of surgery. During the surgery itself, the computer navigation guides are used to position the implants more accurately.

Surfer’s Knee

This usually shows up as a burning-numbness sensation on the inner thigh that can extend below the knee to the inner-calf region. While sitting up and straddling a surfboard in between sets, the saphenous nerve can be compressed. This condition is easily confused with a knee problem because the pain presents in the same region where meniscus tears cause pain. Treatment aims to remove the offending agent (the surfboard), which isn’t always desirable to the patient. You can also try to cushion the inner thigh region in the wetsuit, but this approach is not usually practical.